3.1 Microbial Risks

Microbiological agents are commonly associated with comparatively acute symptoms, which may appear within days or even hours after the consumption of a contaminated food. Some examples of relevant microbial risks that can be transmitted via foods are:

- Pathogenic bacteria: Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter jejuni, Clostridium botulinum, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus cereus, Streptococcus among others.

- Parasitic protozoa and worms: Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, Anisakis simplex, among others.

- Viruses: Hepatitis A, Hepatitis E, Rotavirus, Norwalk virus, among others.

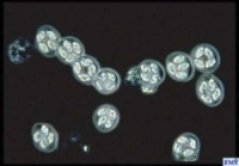

3.1.1 Case Study: Cryptosporidium spp.

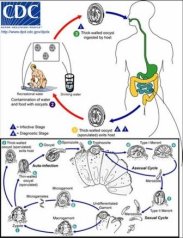

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan pathogen that causes a diarrhoeal illness called cryptosporidiosis. Cryptosporidium does not use an insect vector and is capable of completing its life cycle within a single host, resulting in cyst stages which are excreted in faeces and are capable of transmission to a new host.

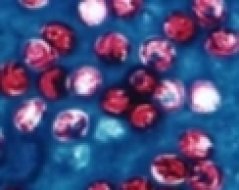

Cryptosporidiosis is typically an acute short-term infection but can become severe and non-resolving in children and immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS and cancer patients. The parasite is transmitted by environmentally hardy cysts (oocysts) that, once ingested, excyst in the small intestine and result in an infection of intestinal epithelial tissue.

Cryptosporidium spp. are recognised as one of the most significant microbiological pathogens that have emerged recently, causing worry within the food processing sector. The main reasons for this are:

- Cryptosporidium can be transmitted through contaminated water and food

- Cryptosporidium is capable of causing a high degree of morbidity (the incidence of the disease) in healthy populations and mortality in susceptible populations

- There is no effective antimicrobial treatment to eliminate Cryptosporidium from the gastrointestinal tract in symptomatic persons.

It was in the 1980s when Cryptosporidium became known as a potential threat to water supplies, especially in the USA and the UK. Since then, other countries have also identified outbreaks of waterborne cryptosporidiosis.

Ever since the identification of Cryptosporidium parvum (C. parvum) as a human pathogen in 1976, several large outbreaks have been documented. The most remarkable outbreak occurred in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA in 1993 where an estimated 403,000 individuals fell ill as a result of a contaminated drinking water supply.

General background

Since the first human cases were documented (1976) C. parvum was labelled as an emerging pathogen. In healthy individuals Cryptosporidium parasites cause acute infections of the digestive system, but in immunocompromised patients they cause a chronic, life-threatening disease. In farm animals, Cryptosporidium parasites cause disorder of the digestive and respiratory system, which leads to poor health of infected animals and considerable economic losses.

So far the genus Cryptosporidium consists of at least 13 recognised species:

- C. hominis (humans)

- C. andersoni (cattle)

- C. baileyi (chicken and some other birds)

- C. canis (dogs)

- C. felis (cats)

- C. galli (birds)

- C. meleagridis (birds and humans)

- C. molnari (fish)

- C. muris (rodents and some other mammals)

- C. parvum (ruminants and humans)

- C. wrairi (guinea pigs)

- C. saurophilum (lizards and snakes)

- C. serpentis (snakes and lizards)

All specifies of Cryptosporidium are obligate (cannot survive without a host), intracellular, protozoan parasites that undergo endogenous development concluding in the production of an encysted stage released in the faeces of the host. Infected hosts produce massive quantities of infective stages (oocysts), which are long-living and extremely resistant to normal water disinfecting techniques. For healthy adults, the infective dose varies from 9-1042 oocysts.

C. parvum can be found extensively in the environment and, often, can also be isolated from surface water. Oocysts are able to survive cool, damp conditions.

Infection and contamination sources

The finding of C. parvum, C. meleagridis, C. felis, C. canis and C. muris in humans implies that farm animals, domestic pets and some wildlife can be potential sources. Direct transmission of C. parvum from animals to humans is well documented.

Many foodborne and waterborne outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis have been caused by C. parvum in North America and Europe, although it is often uncertain whether humans or animals are the source of the contamination.

Food associated with outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis have involved:

- Raw fruits and vegetables (Monge & Chinchilla, 1996; Robertson et al. 2001)

- Raw milk (Gelletli et al. 1997)

- Meat and meat products (Pepin et al. 1997)

- Apple Cider (Millard et al. 1994)

- Contamination by food handlers (Quiroz et al. 2000)

Even though Cryptosporidium oocysts have been identified in various foods, direct incrimination of food in the transmission of cryptosporidiosis is obstructed by:

- The limiting number of oocysts in suspected food samples;

- The lack of an enrichment culture for oocysts recovery;

- The lack of sensitive detection methods.

All this leads to an incidence underestimation.

Sources

- SAFE FOODS: Orlova, O., Kelly, B.G. and Santare, D. (to be published) “Case Study: Cryptosporidium spp.”, Food and Chemical Toxicology.

- Current et al. 1983

- Du Pont et al. 1995

- Fayer et al. 1998

- Fayer et al. 2000

- Haas et al. 1999

- Kosek et al. 2001

- Mackenzie et al. 1994

- Meisel et al. 1976

- Millard et al. 1994

- Miron et al. 1991

- Nimes et al. 1976

- Okhuysen et al. 1999

- Stantic-Pavlinic et al. 1997

- Teunis et al. 1999

- Wikipedia

- Xiao et al. 1999

- Xiao et al 2004